|

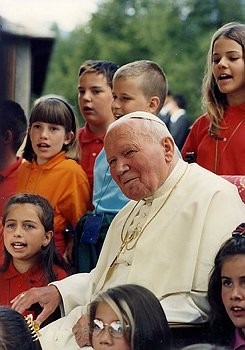

Jan Paweł II LIST DO RODZIN GRATISSIMAM SANE (I)  Fot. vatican.va |

|

Z okazji roku Rodziny 1994 Drogie Rodziny, 1. Obchodzony w Kościele Rok Rodziny stanowi dla mnie dogodną okazję, aby zapukać do drzwi Waszych domów, pragnę bowiem z Wami wszystkimi się spotkać i przekazać Wam szczególne pozdrowienie. Czynię to za pośrednictwem tego Listu, odwołując się do słów wypowiedzianych w Encyklice Redemptor hominis w pierwszych dniach mej Piotrowej posługi. Pisałem wtedy: "Człowiek jest drogą Kościoła"1. To zdanie mówi naprzód o różnych drogach, jakimi chadza człowiek, ażeby równocześnie wyrazić, jak bardzo Kościół stara się iść wraz z człowiekiem po tylu różnych drogach jego ziemskiej egzystencji. Kościół stara się uczestniczyć w radościach i nadziejach, a także w trudach i cierpieniach2 ziemskiego pielgrzymowania ludzi z tym głębokim przeświadczeniem, że to sam Chrystus wprowadził go na te wszystkie drogi: że On sam dał Kościołowi człowieka i równocześnie mu go zadał jako "drogę" jego posłannictwa i posługi. Rodzina drogą Kościoła 2. Pośród tych wielu dróg rodzina jest drogą pierwszą i z wielu względów najważniejszą. Jest drogą powszechną, pozostając za każdym razem drogą szczególną, jedyną i niepowtarzalną, tak jak niepowtarzalny jest każdy człowiek. Rodzina jest tą drogą, od której nie może on się odłączyć. Wszak normalnie każdy z nas w rodzinie przychodzi na świat, można więc powiedzieć, że rodzinie zawdzięcza sam fakt bycia człowiekiem. A jeśli w tym przyjściu na świat oraz we wchodzeniu w świat człowiekowi brakuje rodziny, to jest to zawsze wyłom i brak nad wyraz niepokojący i bolesny, który potem ciąży na całym życiu. Tak więc Kościół ogarnia swą macierzyńską troską wszystkich, którzy znajdują się w takich sytuacjach, ponieważ dobrze wie, że rodzina spełnia funkcję podstawową. Wie on ponadto, iż człowiek wychodzi z rodziny, aby z kolei w nowej rodzinie urzeczywistnić swe życiowe powołanie. Ale nawet kiedy wybiera życie w samotności - to i tutaj rodzina pozostaje wciąż jak gdyby jego egzystencjalnym horyzontem jako ta podstawowa wspólnota, na której opiera się całe życie społeczne człowieka w różnych wymiarach aż do najrozleglejszych. Czyż nie mówimy również o "rodzinie ludzkiej", mając na myśli wszystkich na świecie żyjących ludzi? Rodzina bierze początek w miłości, jaką Stwórca ogarnia stworzony świat, co wyraziło się już "na początku", w Księdze Rodzaju (1,1), a co w słowach Chrystusa w Ewangelii znalazło przewyższające wszystko potwierdzenie: "Tak [...] Bóg umiłował świat, że Syna swego Jednorodzonego dał" (J 3,16). Syn Jednorodzony, współistotny Ojcu, "Bóg z Boga i Światłość ze Światłości", wszedł w dzieje ludzi poprzez rodzinę: "przez wcielenie swoje zjednoczył się jakoś z każdym człowiekiem. Ludzkimi rękoma pracował, [...] ludzkim sercem kochał, urodzony z Maryi Dziewicy, stał się prawdziwie jednym z nas, we wszystkim do nas podobny oprócz grzechu"3. Skoro więc Chrystus "objawia się w pełni człowieka samemu człowiekowi"4, czyni to naprzód w rodzinie i poprzez rodzinę, w której zechciał narodzić się by wzrastać. Wiadomo, że Odkupiciel znaczną część swego życia pozostawał w ukryciu nazaretańskim, będąc "posłusznym" (por. Łk 2,51) jako "Syn Człowieczy" swej Matce Maryi i Józefowi cieśli. Czyż to synowskie "posłuszeństwo" nie jest już pierwszym wymiarem posłuszeństwa Ojcu "aż do śmierci" (Flp 2,8), przez które odkupił świat? Tak więc Boska tajemnica Wcielenia Słowa pozostaje w ścisłym związku z ludzką rodziną. Nie tylko z tą jedną, nazaretańską, ale w jakiś sposób z każdą rodziną, podobnie jak Sobór Watykański II mówi, że Syn Boży przez swoje Wcielenie "zjednoczył się jakoś z każdym człowiekiem"5. Kościół, idąc za Chrystusem, który "przyszedł" na świat, "aby służyć" (Mt 20,28), uważa służbę rodzinie za jedno ze swych najistotniejszych zadań - i w tym znaczeniu zarówno człowiek, jak i rodzina są "drogą Kościoła". Rok Rodziny 3. Z tych właśnie powodów Kościół wita z radością inicjatywę Międzynarodowego Roku Rodziny 1994, podjętą przez Organizację Narodów Zjednoczonych. Świadczy ona o tym, jak istotna i podstawowa jest sprawa rodziny dla wszystkich społeczeństw i państw wchodzących w skład ONZ. Jeśli Kościół pragnie w tej inicjatywie narodów uczestniczyć, to dlatego, że sam został posłany przez Chrystusa do "wszystkich narodów" (por. Mt 28,19). Nie po raz pierwszy zresztą Kościół na swój sposób podejmuje międzynarodowe inicjatywy ONZ. Wystarczy wspomnieć, choćby Międzynarodowy Rok Młodzieży w roku 1985. W ten sposób zamysł wyrażony w Konstytucji soborowej Gaudium et spes - zamysł tak drogi papieżowi Janowi XXIII - znajduje właściwe sobie urzeczywistnienie: Kościół jest obecny w świecie współczesnym. Tak przeto w uroczystość Świętej Rodziny 1993 rozpoczął się w całej Wspólnocie kościelnej "Rok Rodziny" jako jeden ze znaczących etapów przygotowania do Wielkiego Jubileuszu roku 2000, który wyznacza kres drugiego i początek trzeciego tysiąclecia od narodzenia Jezusa Chrystusa. Rok Rodziny skierowuje nasze myśli i serca w stronę Nazaretu, gdzie dnia 26 grudnia ubiegłego roku został on oficjalnie zainaugurowany Ofiarą Eucharystyczną, sprawowaną przez Legata papieskiego. Jest rzeczą ważną przez cały ten rok odwoływać się do świadectw miłości i troski Kościoła o rodzinę ludzką. Miłości i troski wyrażającej się w sposób znamienny już od samych początków chrześcijaństwa, kiedy rodzina była określana jako "domowy Kościół". W naszych czasach często wracamy do tego wyrażenia "Kościół domowy", przyjętego przez Sobór6, pragniemy bowiem, ażeby to, co się w nim zawiera, nigdy nie uległo "przedawnieniu". Pragnienia tego nie osłabia świadomość bardzo odmiennych warunków, w jakich bytują ludzkie rodziny w świecie współczesnym. Właśnie dlatego tak bardzo znamienny jest tytuł "Poparcie należne godności małżeństwa i rodziny"7, którym posłużył się Sobór w Konstytucji duszpasterskiej Gaudium et spes dla wyrażenia zdań Kościoła w tej szerokiej dziedzinie. Kolejnym ważnym punktem odniesienia po Soborze jest posynodalna Adhortacja Apostolska Familiaris consortio z 1981 roku. W tekście tym wyraża się rozległe i zróżnicowane doświadczenie rodziny, która wśród tylu ludów i narodów wciąż pozostaje na wszystkich kontynentach "drogą Kościoła", a w jakimś znaczeniu staje się nią jeszcze bardziej tam, gdzie rodzina doznaje wewnętrznych kryzysów, gdy narażona bywa na szkodliwe wpływy kulturowe, społeczne i ekonomiczne, które nie tylko osłabiają jej spoistość, ale wręcz utrudniają jej powstanie. Modlitwa 4. Niniejszy List pragnę skierować nie do rodziny "in abstracto", ale do konkretnych rodzin na całym globie, żyjących pod każdą długością i szerokością geograficzną, pośród całej wielości kultur oraz ich dziedzictwa historycznego. Właśnie miłość, jaką Bóg "umiłował świat" (J 3,16) - ta miłość, jaką Chrystus "do końca [...] umiłował" (J 13,1) każdego i wszystkich, pozwala na takie otwarcie i na takie przesłanie do każdej rodziny, stanowiącej "komórkę" w wielkiej i powszechnej "rodzinie" ludzkości. Bóg, Stwórca wszechświata oraz Słowo Wcielone, Odkupiciel ludzkości są źródłem otwarcia się na wszystkich ludzi jako braci i siostry, i skłaniają nas do obejmowania ich wszystkich tą modlitwą, która zaczyna się od słów "Ojcze nasz". Modlitwa zawsze sprawia, że Syn Boży jest wśród nas: "gdzie są dwaj lub trzej zebrani w imię moje, tam jestem pośród nich" (Mt 18,20). Niechaj ten List do Rodzin stanie się zaproszeniem Chrystusa do każdej ludzkiej rodziny, a poprzez rodzinę zaproszeniem Go do wielkiej rodziny narodów, abyśmy z Nim razem mogli powiedzieć w prawdzie: "Ojcze nasz!" Trzeba, ażeby modlitwa stała się dominantą Roku Rodziny w Kościele: modlitwa rodziny, modlitwa za rodziny, modlitwa z rodzinami. Rzecz znamienna, że właśnie w modlitwie i przez modlitwę człowiek odkrywa w sposób najprostszy i najgłębszy zarazem właściwą sobie podmiotowość: ludzkie "ja" potwierdza się jako podmiot najłatwiej wówczas, gdy jest zwrócone do Boskiego "Ty". Odnosi się również do rodziny. Jest ona nie tylko podstawową "komórką" społeczeństwa, ale posiada równocześnie właściwą sobie podmiotowość. I ta podmiotowość rodziny również znajduje swe pierwsze i podstawowe potwierdzenie, a zarazem umocnienie, gdy spotyka się we wspólnym wołaniu "Ojcze nasz". Modlitwa służy ugruntowaniu duchowej spoistości rodziny, przyczyniając się do tego, że rodzina staje się silna Bogiem. W liturgii Sakramentu Małżeństwa celebrans modli się słowami: "Prosimy Cię, Boże, ześlij swoje błogosławieństwo na tych nowożeńców [...] i wlej w ich serca moc Ducha Świętego"8. Trzeba, aby z tego "nawiedzenia serc" płynęła wewnętrzna moc ludzkich rodzin - moc jednocząca je w miłości i prawdzie. Miłość i troska o wszystkie rodziny 5. Niech Rok Rodziny stanie się powszechną i nieustanną modlitwą "Kościołów domowych" i całego Ludu Bożego! Niech w tej modlitwie znajdą swoje miejsce również rodziny zagrożone czy chwiejące się, również i te zniechęcone, rozbite lub znajdujące się w sytuacjach, które Familiaris consortio określa jako "nieprawidłowe"9. Trzeba, ażeby czuły się ogarnięte miłością i troską ze strony braci i sióstr. Równocześnie modlitwa Roku Rodziny niech będzie odważnym świadectwem rodzin, które we wspólnocie rodzinnej znajdują spełnienie swego życiowego powołania: ludzkiego i chrześcijańskiego. A ileż ich jest wszędzie, w każdym narodzie, diecezji i parafii! Pomimo wszystkich "sytuacji nieprawidłowych" wolno żywić przekonanie, że te właśnie rodziny stanowią "regułę". Ich świadectwo jest ważne także dlatego, ażeby człowiek, który się w nich rodzi i wychowuje, wszedł bez wahania czy zwątpienia na drogę dobra, jakie jest wpisane w jego serce. Na rzecz takiego zwątpienia zdają się usilnie pracować różne programy przy pomocy potężnych środków, jakie pozostają do ich dyspozycji. Niejednokrotnie trudno się oprzeć przeświadczeniu, iż czyni się wszystko, aby to, co jest "sytuacją nieprawidłową", co sprzeciwia się "prawdzie i miłości" we wzajemnym odniesieniu mężczyzn i kobiet, co rozbija jedność rodzin bez względu na opłakane konsekwencje, zwłaszcza gdy chodzi o dzieci - ukazać jako "prawidłowe" i atrakcyjne, nadając temu zewnętrzne pozory fascynacji. W ten sposób zagłusza się ludzkie sumienie, zniekształca to, co prawdziwie jest dobre i piękne, a ludzką wolność wydaje się na łup faktycznego zniewolenia. Jakże aktualne stają się wobec tego Pawłowe słowa o wolności, do której wyzwala nas Chrystus, oraz o zniewoleniu przez grzech (por. Ga 5,1)! Widać jak bardzo odpowiedni, a nawet potrzebny jest Rok Rodziny w Kościele. Jak bardzo konieczne jest świadectwo tych wszystkich rodzin, które znajdują w nich prawdziwe spełnienie swego życiowego powołania. Jak bardzo też pilna jest ta - przez cały glob idąca i narastająca - wielka modlitwa rodzin, w której wyraża się dziękczynienie za miłość w prawdzie, za "nawiedzenie serc" przez Ducha-Pocieszyciela10, za obecność Chrystusa pośród rodziców i dzieci: Chrystusa Odkupiciela i Oblubieńca, który "umiłował nas aż do końca" (por. J 13,1). Jesteśmy głęboko przekonani, że miłość ta jest największa (por. 1 Kor. 13,13). Wierzymy, iż zdolna jest ona przewyższyć to wszystko, co nie jest miłością. Niech wznosi się modlitwa Kościoła, modlitwa rodzin - wszystkich "domowych Kościołów" i niech będzie w tym roku słyszana, naprzód przez Boga, a także przez ludzi! Ażeby nie popadali w zwątpienie. Ażeby nie ulegali mocy pozornego dobra, które stanowi sam rdzeń każdej pokusy. W Kanie Galilejskiej, dokąd Jezus był zaproszony na gody weselne, słyszymy wezwanie Jego Matki: "Zróbcie wszystko, cokolwiek wam powie" (J 2,5). To wezwanie odnosiło się wówczas do sług weselnych. Odnosi się ono jednak pośrednio do nas wszystkich, którzy oto wkraczamy w Rok Rodziny. To, co mówi do nas Chrystus w tym momencie, zdaje się być w szczególności właśnie wezwaniem do wielkiej modlitwy z rodzinami i za rodziny. Matka Chrystusa zaprasza nas, abyśmy przez tę modlitwę zjednoczyli się z Jej Synem, który miłuje każdą ludzką rodzinę. Dał temu wyraz zaraz na początku swej odkupieńczej misji, właśnie przez swą uświęcającą obecność w Kanie Galilejskiej. Ta Chrystusowa obecność trwa. Prośmy za wszystkie rodziny całego świata, modląc się przez Niego, z Nim i w Nim do Ojca, "od którego bierze nazwę wszelki ród na niebie i na ziemi" (Ef 3,15). I |